Not From Man: Five Evidences That the Gospel Stands on Divine Authority

Have you ever had someone try to convince you that what you believed wasn’t quite enough? That you needed to add something to it? To add some extra step, some additional requirement, before it could really count?

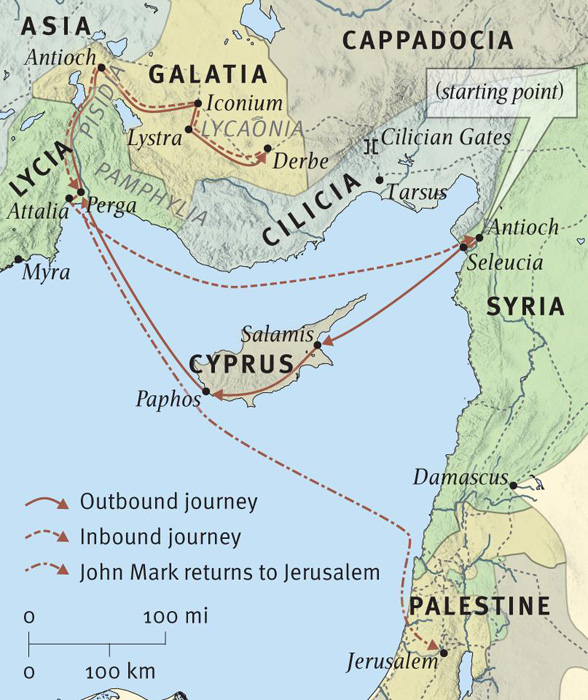

That’s exactly what was happening to the Galatian believers. Not long before Paul wrote to them, he and Barnabas had come through their cities preaching the gospel — that Jesus was the promised Messiah, that he died for their sins according to the Scriptures, rose from the dead, and could set them free. These believers saw Paul persecuted for this message, watched him get stoned and left for dead, and then witnessed him get back up and keep going. They believed, and it changed their lives.

But then the Judaizers showed up. Using the same Old Testament source material, they told these young believers that Paul had left some things out. If they really wanted to please God, they needed circumcision. They needed the law. They needed more. And in a time before the New Testament had been written, when you couldn’t just open your Bible and check, that kind of claim created real confusion. In Galatians 1:11–2:10, Paul responds with evidence.

A Thesis Worth Proving

Paul opens with a bold claim: “The gospel which was preached by me is not according to man. For I neither received it from man, nor was I taught it, but I received it through a revelation of Jesus Christ” (Galatians 1:11–12). He’s tracing the gospel all the way back to its origin. Most of us heard the gospel from other people. A parent, a pastor, a friend. There’s nothing wrong with that. But Paul wants the Galatians to understand that the message itself didn’t start with human beings. It started with God, was proven through the person of Jesus Christ and his resurrection from the dead, and was entrusted to witnesses who carry it forward. Not as their own message to edit, but as a divine message to faithfully proclaim.

From here, Paul builds his case with five key pieces of evidence that his original audience could have personally verified.

Evidence #1: A Life That Only God Could Change

Paul’s first appeal is to his own transformation. “You have heard of my former manner of life in Judaism,” he writes, “how I used to persecute the church of God beyond measure and tried to destroy it” (Galatians 1:13). This wasn’t ancient history to the Galatians. They knew his reputation. Paul had been a rising star in Judaism, a religious celebrity who studied under famous teachers and made it his mission to imprison and even kill believers. Then he met the risen Jesus, and everything changed.

A changed life is powerful evidence, especially when the people hearing about it actually knew you before. Someone on the street might shrug off a conversion story. But the people who knew Paul before? After more than a decade of sustained, costly faithfulness? That’s a different conversation entirely.

Continue reading